Joining Up

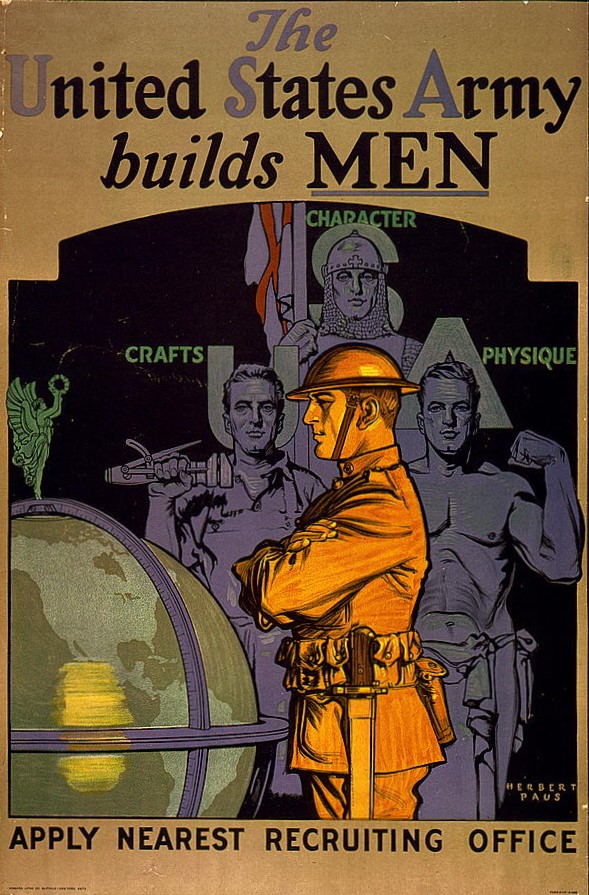

By the time of the First World War, Americans “generally equated manliness with physical and moral courage and a sense of honor with personal reputation.”1 These beliefs of manliness were closely tied with military service and many young men enlisted to serve their country and prove their worth as a man through combat.2 This desire to embody manliness was so great that many young men did whatever they could to join the military. Those who had failed Army standards for things including height and weight or had serious medical conditions, like a heart murmur, called in whatever favors they could in order to join the military.3

While these motivations for joining the military were applicable to all young American men, white and black, African Americans also had an additional motivating factors. Some, inspired by the writings of W.E.B. DuBois, believed that their military service in Europe would lead to “greater equality in the United States” for African Americans.4 Others wished to show that they were just as manly as white Americans and disprove the “white stereotypes about black innate inferiority and cowardice.”5 While a majority of African Americans who served during World War I did not see combat, those that did showed that they were just as brave and manly as their white comrades.

African American Combat Record

Since the American Civil War, African American soldiers had proved themselves in combat. The Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments and the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments fought Native American tribes in the West after the Civil War, served in the Spanish-American War, fought in the Philippines, and deployed to Mexico to help track down Pancho Villa, the Mexican revolutionary. Despite their combat experience and reputation, these units were often relegated to garrison duty and border security in Mexico, Hawaii, and the Philippines.6 During the First World War, African American units performed admirably and heroically in combat. The 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, including the famous 369th Infantry Regiment (the Harlem Hellfighters), were attached to the French Army and fought side by side with French troops until the end of the war. During their service with the French, numerous African American soldiers from the 92nd and 93rd received military honors and awards, including the Croix de Guerre, France’s highest military honor.7

A Jim Crow Army & SATC

Given the expected casualty rates of junior officers, the dramatic expansion of the army, and the history of service of the African Americans in combat, it would have been logical for the War Department to tap into historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) as a resource for officers and specialists. The 92nd and 93rd already had a few black junior officers (lieutenants and captains), and the rapid expansion of HBCUs between 1845 and 1915 gave the War Department around eighty-eight schools for potential collegiate SATC units.8

However, the Army was imbued with white supremacist attitudes and the War Department initially felt that African Americans “lacked the requisite attributes of manhood – mental sturdiness, self-control, objectivity – to become quality officers.”9 Despite the legacy and combat record of African American troops and the heroic exploits of the 92nd and 93rd Division, the War Department perpetuated the negative stereotypes about African American cowardliness and lack of manliness. Additionally, the War Department, “paternalistically assumed that only white officers could effectively manage back troops.”10 This belief led to the establishment of a single officer training camp for African Americans at Fort Des Moines in Iowa. For the SATC, this view of African American officers and soldiers meant that only twenty-five HBCUs received approval for SATC units; seventeen collegiate A Sections and eight vocational B Sections.11

Notes:

- Richard S. Faulkner, Pershing’s Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 20–21.

- Richard S. Faulkner, Pershing’s Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 22–23.

- Richard S. Faulkner, Pershing’s Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 24.

- Richard S. Faulkner, Pershing’s Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 245.

- Richard S. Faulkner, Pershing’s Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 245.

- Chad Louis Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 66.

- “The Buffalo Soldiers in WWI (U.S. National Park Service),” accessed March 2, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-buffalo-soldiers-in-wwi.htm; “Remembering the Harlem Hellfighters,” National Museum of African American History and Culture, accessed March 2, 2023, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/remembering-harlem-hellfighters.

- Bobby L. Lovett, America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A Narrative History from the Nineteenth Century into the Twenty-First Century (Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 2011), 370–72; Chad Louis Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 67,129.

- Chad Louis Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 39.

- Chad Louis Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 39.

- Chad Louis Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 41-43; Student Army Training Corps Descriptive Circular dated October 14, 1918, Box 3, Folder 8, Records of the Dean of the College, Theodorick Pryor Campbell, RG 11/1, Special Collections and University Archives, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA.