The Poppies Blow Between the Crosses, Row on Row1

In August 1915, Major Spencer Crosby, the American military attaché in Paris, sent a report to Washington, D.C. that detailed French casualties during two months of fighting near the French town of Arras. He reported that the French lost between 60,000 and 85,000 men, but also acknowledged that the number of casualties could be as high as 200,000, double the size of the entire American Army and Reserves in 1914. Maj. Crosby’s report did not seem to influence War Department decisions in 1914, but by 1917, his report was more important than ever as American troops and officers entered combat.2

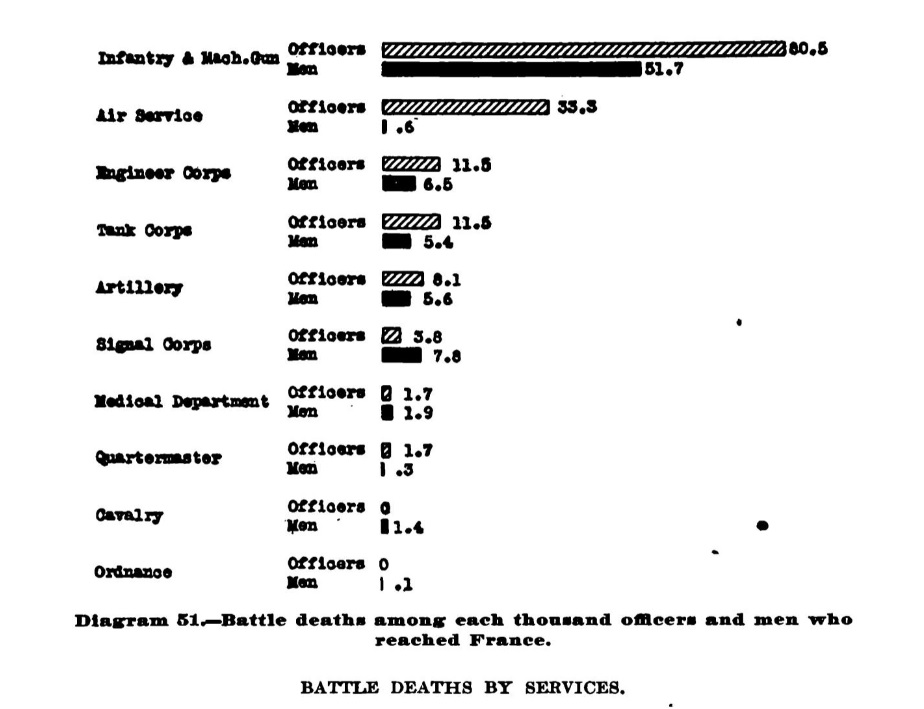

Though only a few American units fought in Europe in 1917, the casualty rates were shocking to the War Department. Utilizing data from the other Allied Powers and their own limited combat experience, the American Expeditionary Force General Headquarters estimated that they would lose approximately seventy-five percent of their junior officers every year.4 The lack of experience in trench warfare and the inadequate training that American officers received contributed heavily to casualty rates of both enlisted men and officers. The American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was losing so many officers in 1917 that as a stop-gap measure, a school was established in France in October to train enlisted men as replacement officers.5 The problem of high officer casualty rates would continue throughout 1917 and increase in 1918 as the German spring offensive forced more American units into action.

Allied Offensive of Spring 1919 & the Occupation of Germany

In 1918, the Allied Powers (France, Great Britain, and the United States) expected the war to continue into 1919 and planned to launch an offensive the next spring.6 Because Germany switched to a defensive strategy in the later stages of the war, the United States increased the number of troops they sent to Europe. By spring 1919, the AEF was anticipated to have eighty divisions to launch an offensive against the Germans.7 More American troops meant more officers which in turn meant more officer casualties.

There was also a fear that the German Army would collapse and resort to guerrilla warfare to prolong the fighting. Colonel George C. Marshall, who would later become Chief of Staff of the United States Army during World War II, wrote in his memoirs of World War I that if the German army turned to guerrilla warfare, the Allies “would have had to occupy all of Germany, a difficult and lengthy task.”8 Fighting a guerrilla war in unfamiliar territory and occupying Germany would require additional troops and officers.

In preparation for the expected high officer causality rate, the War Department looked for ways to increase the production of new officers. Despite increasing the commission rate of Officer Training Camp (OTC) graduates and expanding the size of each OTC class, they needed a better system for training both frontline officers and specialty officers, such as artillerymen and engineers. Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) programs were multiyear and would not produce the necessary numbers fast enough. To solve this problem, the War Department replaced ROTC with a new program, the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC).

Notes:

- This is a line from the poem “In Flander’s Fields” written by Canadian Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae after the second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915. For more information visit: https://www.britishlegion.org.uk/get-involved/remembrance/about-remembrance/in-flanders-field.

- Faulkner, The School of Hard Knocks: Combat Leadership in the American Expeditionary Forces, 23.

- Leonard Porter Ayres, The War with Germany: A Statistical Summary (Washington, D.C., 1919), page 121, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc276266/.

- Faulkner, 176.

- Faulkner, 175.

- George C. Marshall, Memoirs of My Service in the World War, 1917-1918 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976), 175; C&Rsenal, “Small Arms of WWI Primer 065: The Pedersen Device,” uploaded December 5, 2017, YouTube video, 1:14:49, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M637KpEP1_E, 38:30-38:55.

- Geoffrey Wawro, Sons of Freedom: The Forgotten American Soldiers Who Defeated Germany in World War I, (New York: Basic Books, 2018), 440, 458.

- Marshall, Memoirs of My Service in the World War, 1917-1918, 203–4; Wawro, Sons of Freedom: The Forgotten American Soldiers Who Defeated Germany in World War I, 479.