National Training Detachment Lectures

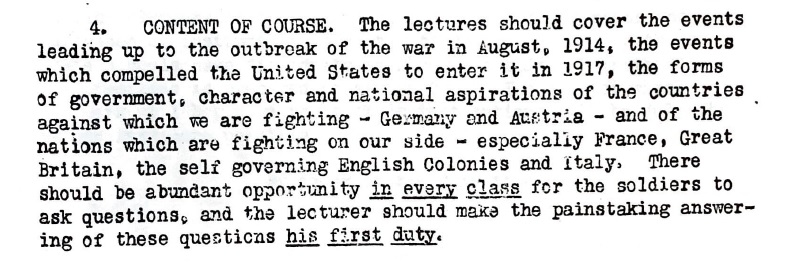

On June 21, 1918, the Committee on Education and Special Training (CEST) sent a memo to all colleges and universities with National Training Detachments (NTD) about the introduction of a new lecture series. These lectures were designed to “enhance the morale of the soldiers under training by giving them an idea of what the war is about and of the supreme importance to our democracy of the cause for which we are fighting.”1 These lectures encouraged student discussion and focused on everything from the events of the war to the goals of the participant countries. These lectures were the first iteration of the War Aims Course, which would become a required class for all members of the SATC.

SATC War Issues Course

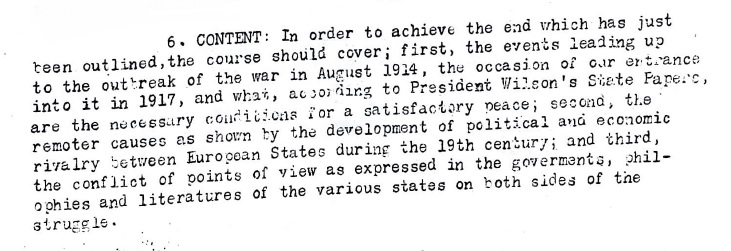

Once the CEST established the SATC, they introduced a modified version of the NTD lecture series on August 27, 1918. Now structured as a full course required for every soldier in the SATC, this new War Aims Course, later renamed to War Issues Course, was also designed to enhance the morale of SATC members. Unlike its previous iteration, the War Issues Course only focused on the “remote and immediate causes of the war and on the underlying conflict of points of view as expressed in the governments, philosophies, and literatures [sic] of the various states on both sides of the struggle.”3

Recognizing that the twenty year old SATC members would only be in school for three months, the CEST prioritized the historical and economic causes of the war for the first three month term. The second term would focus on the perspectives of each participant by looking at the each nation’s government and the third term would examine philosophies and literature from each participant nation.5

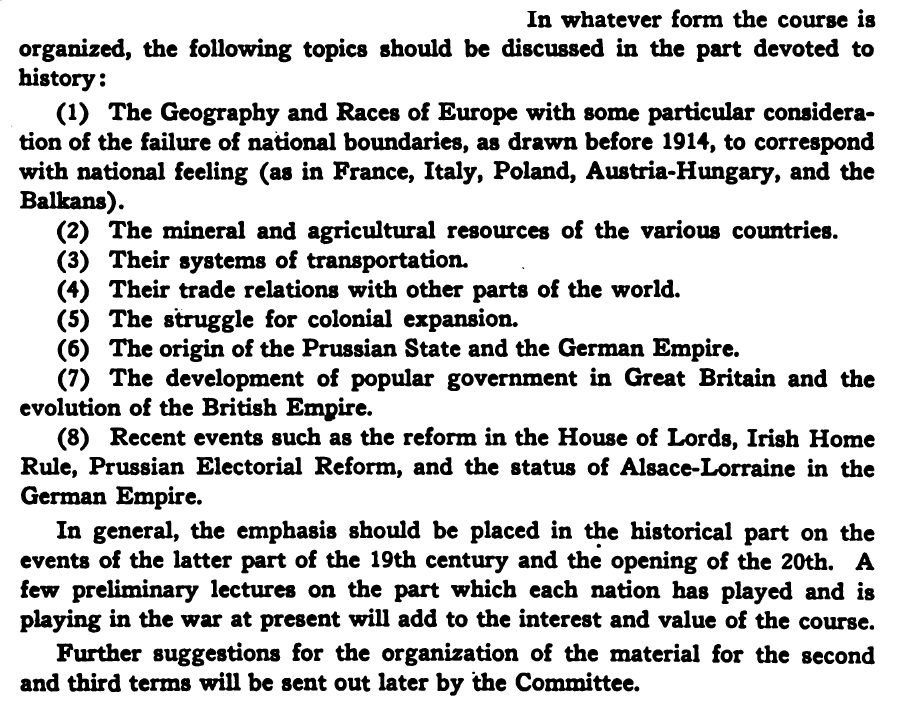

On September 18, 1918, the CEST informed professors teaching the course that they would be sent a copy of Albert E. McKinley’s Collected Materials for the Study of the War as a basis for instruction, though other works could be used.6 The CEST also outlined the historical content professors should cover:

The CEST wanted SATC students to engage with the material and provided several suggestions and mandates to help. First, they recommended combining the War Issues Course with English Composition so that students could think more about the material, both in class discussions and in writing assignments. Second, they required courses to have no more than 25 to 50 men or to have large classes with smaller discussion sections to allow students to ask as many questions as they wanted. Third, they recommended that instructors teaching the course should be good lecturers, familiar with the subject matter, and have the ability to draw out questions from their students. The CEST felt that these stipulations would produce the best result and “make the issues of the war a living reality to each man.”8

Legacy

Like many other aspects of the SATC, the War Issues Course did not last much longer after the Armistice and demobilization of the SATC in late 1918. But the idea of educating soldiers about the background of a war they were fighting and boosting morale carried on. During the Second World War, filmmaker Frank Capra was asked by General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff, to make a series of propaganda films to help soldiers understand the events of the war and why the United States joined the fighting.11

Capra produced seven films, each fifty minutes long, and titled the series Why We Fight. Capra outlined the films in his own words:

| Film Title | Summary |

| Prelude to War | Presenting a general picture of two worlds; the slave and the free, and the rise of totalitarian militarism from Japan’s conquest of Manchuria to Mussolini’s conquest of Ethiopia. |

| The Nazis Strike | Hitler rises. Imposes Nazi dictatorship on Germany. Goose-steps into Rhineland and Austria. Threatens war unless given Czechoslovakia. Appeasers oblige. Hitler invades Poland. Curtain rises on the tragedy of the century – World War II. |

| Divide and Conquer | Hitler occupies Denmark and Norway, outflanks Maginot Line, drives British Army into North Sea, forces surrender of France. |

| Battle of Britain | Showing the gallant and victorious defense of Britain by Royal Air Force, at a time when shattered by unbeaten British were only people fighting Nazis. |

| Battle of Russia | History of Russia; people, size, resources, wars. Death struggle against Nazi armies at gates of Moscow and Leningrad. At Stalingrad, Nazis put through meat grinder. |

| Battle of China | Japan’s warlords commit total effort to conquest of China. Once conquered, Japan would use China’s manpower for the conquest of Asia. |

| War Comes to America | Dealt with who, what, where, why, and how we came to be the U.S.A. – the oldest major democratic republic still living under its original constitution. But the heart of the film dealt with the depth and variety of emotions with which Americans reacted to the traumatic events in Europe and Asia. How our convictions slowly changed from total non-involvement to total commitment as we realized that loss of freedom anywhere increased the danger to our own freedom. This last film of the series was, and still is, one of the most graphic visual histories of the United States ever made. |

These seven training films, originally intended for use by the Army, were also used by Navy, Marines, and the Coast Guard, as well as by Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. As Capra stated, “Thus, the We Why Fight series became our official, definitive answer to: What was the [United State’s] government policy during the dire decade 1931-41? . . . By extrapolation, the film series was also accepted as the official policy of our allies.”13

Notes:

- Letter from Major Grenville Clark, CEST Secretary to Institutions where Training Detachments are located dated June 21, 1918, Box 3, Folder 8, Records of the Dean of the College, Theodorick Pryor Campbell, RG 11/1, Special Collections and University Archives, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA.

- Letter from Major Grenville Clark, CEST Secretary to Institutions where Training Detachments are located dated June 21, 1918, Box 3, Folder 8, Records of the Dean of the College, Theodorick Pryor Campbell, RG 11/1, Special Collections and University Archives, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA.

- Letter from Major Grenville Clark, CEST Secretary to Institutions where Units of the Student Army Training Corps are located dated August 27, 1918, Box SF047, Folder SATC Correspondence 1918 May-Aug, World War I Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) and Training Camps Records, 1917-1919, Office of the Superintendent, administrative subject files, Virginia Military Institute Archives, Lexington, VA.

- Letter from Major Grenville Clark, CEST Secretary to Institutions where Units of the Student Army Training Corps are located dated August 27, 1918, Box SF047, Folder SATC Correspondence 1918 May-Aug, World War I Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) and Training Camps Records, 1917-1919, Office of the Superintendent, administrative subject files, Virginia Military Institute Archives, Lexington, VA.

- Letter from Major Grenville Clark, CEST Secretary to Institutions where Units of the Student Army Training Corps are located dated August 27, 1918, Box SF047, Folder SATC Correspondence 1918 May-Aug, World War I Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) and Training Camps Records, 1917-1919, Office of the Superintendent, administrative subject files, Virginia Military Institute Archives, Lexington, VA.

- The Advisory Board, Committee on Education and Special Training. A Review of Its Works during 1918 (Washington, 1919), 128-129, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000488027. A digitized copy of Albert E. McKinley’s Collected Materials for the Study of the War can be found here: https://archive.org/details/collectedmateria00mckiuoft/page/n5/mode/2up.

- The Advisory Board, Committee on Education and Special Training. A Review of Its Works during 1918 (Washington, 1919), 129, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000488027.

- Letter from Major Grenville Clark, CEST Secretary to Institutions where Units of the Student Army Training Corps are located dated August 27, 1918, Box SF047, Folder SATC Correspondence 1918 May-Aug, World War I Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) and Training Camps Records, 1917-1919, Office of the Superintendent, administrative subject files, Virginia Military Institute Archives, Lexington, VA.

- Letter from Major Grenville Clark, CEST Secretary to Institutions where Units of the Student Army Training Corps are located dated August 27, 1918, Box SF047, Folder SATC Correspondence 1918 May-Aug, World War I Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) and Training Camps Records, 1917-1919, Office of the Superintendent, administrative subject files, Virginia Military Institute Archives, Lexington, VA.

- The Advisory Board, Committee on Education and Special Training. A Review of Its Works during 1918 (Washington, 1919), 128-132, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000488027.

- Peter C. Rollins, “Frank Capra’s Why We Fight Film Series and Our American Dream,” Journal of American Culture 19, no. 4 (1996): 81,83, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734X.1996.1904_81.x.

- Frank Capra, The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography (New York, Macmillan, 1971), 335–36, http://archive.org/details/nameabovetitleau00caprrich.

- Frank Capra, The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography (New York, Macmillan, 1971), 336, http://archive.org/details/nameabovetitleau00caprrich.